When we arrived in London, we knew very little about the institution of the English pub and even less about the dark, warm, uncarbonated ales that they serve. Of course, we were not new to beer culture. As former residents of New Orleans (we miss gumbo a lot) and New England, we were familiar with some of the most common American microbrews, Abita and Sam Adams, and during our domestics travels, we always seek out new (to us) local beers like Victory in Philadelphia, Bell's in Michigan, and the selections at the aforementioned Piece in Chicago. Still, while British lagers have long been familiar to the American palate, ales, bitters, stouts, milds and porters are harder to come by and the legal and cultural relics of prohibition in many states have prevented the Yankee bar from claiming the same social and cultural significance as the English pub.

When we arrived in London, we knew very little about the institution of the English pub and even less about the dark, warm, uncarbonated ales that they serve. Of course, we were not new to beer culture. As former residents of New Orleans (we miss gumbo a lot) and New England, we were familiar with some of the most common American microbrews, Abita and Sam Adams, and during our domestics travels, we always seek out new (to us) local beers like Victory in Philadelphia, Bell's in Michigan, and the selections at the aforementioned Piece in Chicago. Still, while British lagers have long been familiar to the American palate, ales, bitters, stouts, milds and porters are harder to come by and the legal and cultural relics of prohibition in many states have prevented the Yankee bar from claiming the same social and cultural significance as the English pub.The internet is full of blogs and websites by and for aficionados of British pubs and ales. Some careful drinkers document every pint they sink in every pub; their sites are sources that cater primarily to the truly dedicated, like the group of eight middle-aged men we met on the train to Bath last Saturday who were undertaking a twelve-pub (!) crawl of the city, beginning at 11 in the morning. As relative rookies, and Americans to boot, we ventured forth into the pub-o-sphere armed with little more than our (fleeting) wits and a powerful thirst for beer and insight. After many arduous hours of painstaking research, we are now ready to share what will undoubtedly be the first of several installments elucidating what we've learned in our search for the perfect pint.

First, a (very) brief history may be useful. Beer was invented in ancient Egypt and brought to Britain by the Arabs who occupied Spain during the Middle Ages. London's first drinking establishments were the tabernae erected by the Romans; after the demise of the empire, they diversified into taverns, alehouses and inns. The pub (short for Public House) as we know it dates to the Victorian era, when it established itself as the social center of virtually every British village. In larger cities, neighborhood pubs known as "locals" proliferated and became the hub of each area of town; in the 1870s, the St. James area of Westminster boasted one pub for every 116 residents. Today, most pubs in England fall into one of three categories:

- The corporately owned chain pub, which offers a standard (predictable) selection of beers and microwaved grub. These pubs are a last resort for beer snobs, or anyone who wants to avoid leaving with a pounding headache.

- The brewery-owned pub, serving a selection of ales from a specific brewery (Fuller's, Young's & Adnams, for example) and often a "guest ale" or two.

- The independent pub, where they pour whatever they please.

The latter two of these pub types are likely to meet the first of our three criteria for choosing a pub: real ale. Ale is made from barley malt, pumped by hand from a cask in the pub's cellar and served at room temperature. Another authentic option, the bitter, is made by adding hops during fermentation. Our American readers are probably familiar with India Pale Ale (IPA); this was developed when sailors charged with the task of transporting bitter by ship to homesick Brits in India solved the problem of spoilage by infusing the beer with extra hops, which acted as a preservative. If you like IPA, you would have made a great colonial administrator.

Our second criterion is harder to quantify, but may be summed up in one word, atmosphere, atmosphere, atmosphere. We look for two main qualities:

- Coziness: fireplaces, candles, low ceilings, anything to make hunkering down on a cold grey London evening when it gets dark at 4 PM just a little more bearable.

- Character: something architecturally or decoratively unique. A favorite Soho pub, the Dog and Duck, has walls lined from floor to ceiling with ceramic tiles. Bill Bryson says that this style of pub makes him feel like he's drinking in Prince Albert's loo. If you're of this mind, a punched tin ceiling, sunny conservatory or garden, pots of geraniums or a smiling Polish barmaid can help to meet this criterion. Some traditional architectural hallmarks include frosted or etched glass windows, "snob screens" (eye level barriers atop the bar, protecting the nobility from potentially polluting contact with the hoi polloi providing their refreshment) and other remnants of wooden or glass structures which at one time would have divided the drinking space into public (exclusively male) and private (coed) rooms. A great name - Laura's favorite is "The Frog and Trousers" - and an interesting coat of arms can also assist a pub in its quest for atmosphere.

Our third criterion is the most subjective: the unique appeal of a pub. What makes a pub great? How can a neighborhood joint make you feel like there's nowhere in the world you'd rather be? This is the mystery element. For us, this appeal often lies in the friendliness of staff, as well as the nature of the food available. In the burgeoning number of gastropubs, fantastic and unusual pub grub is often to be had; less gourmet but equally tasty fare can also be found in institutions like the charmingly bizarre Churchill Arms in Notting Hill, which serves incredible (and super-cheap!) Thai food in a Victorian glass conservatory at its rear.

We mentioned that this may be the first of many posts on the subject, not because we anticipate a need for heavy drinking in the near future, but because creating a personal pub taxonomy is tricky. Our friend John has listened carefully to our thoughts on the subject and laughed to himself over the brim of his pint glass. In his six years in London, he has developed a system of pub classification which dictates where to drink a first, second, third or seventh pint, depending on time of day, day of the week, month of the year, the weather and his disposition at the moment of consumption - among other things. So, needless to say, this is complicated stuff and we welcome your comments, criticisms, insights and advice. Better yet, take us out to your favorite pub and buy us a pint! Or at least tell us where it is...

Happy Halloween!

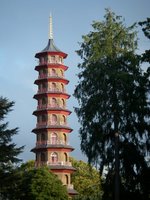

There were, admittedly, some pecularities in the English version of autumnal celebration: a twenty-foot-high pumpkin man looming over the apple cider table (Laura, usually not a Halloween enthusiast, is writing to Congress immediately to lobby for the introduction of NEA grants for the encouragement of an American school of pumpkin sculpture, which we now see can be a truly moving form of artistic expression), as well as a pagoda and a Japanese garden. We spied a pair of rather forward peacocks wandering through the cafe, joining in the universal search for snacks. A tour through the Palm House's dramatic jungle plants, unapologetically appropriated by monocled botanists at a time when imperial Britain enjoyed all the spoils of balmier lands, provided an unexpected tropical counterpart to the chilly air and falling leaves outside.

There were, admittedly, some pecularities in the English version of autumnal celebration: a twenty-foot-high pumpkin man looming over the apple cider table (Laura, usually not a Halloween enthusiast, is writing to Congress immediately to lobby for the introduction of NEA grants for the encouragement of an American school of pumpkin sculpture, which we now see can be a truly moving form of artistic expression), as well as a pagoda and a Japanese garden. We spied a pair of rather forward peacocks wandering through the cafe, joining in the universal search for snacks. A tour through the Palm House's dramatic jungle plants, unapologetically appropriated by monocled botanists at a time when imperial Britain enjoyed all the spoils of balmier lands, provided an unexpected tropical counterpart to the chilly air and falling leaves outside.

were instead met with the sight of these monstrous metal vats. Hugo's rapture was undiminished, and he gleefully filled a large glass with the alarmingly purple concoction and invited us all to take a swig (with the slightly alarming warning that we were not under any circumstances to swallow it; perhaps it magically confers a perfect French accent, or some other such carefully guarded secret). We all spit it onto the floor with gleeful abandon.

were instead met with the sight of these monstrous metal vats. Hugo's rapture was undiminished, and he gleefully filled a large glass with the alarmingly purple concoction and invited us all to take a swig (with the slightly alarming warning that we were not under any circumstances to swallow it; perhaps it magically confers a perfect French accent, or some other such carefully guarded secret). We all spit it onto the floor with gleeful abandon.